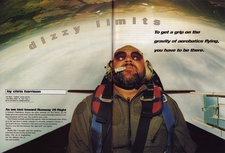

Dizzy Limits

As we taxi toward Runway 29 Right at Sydney's Bankstown Airport, my pilot, aerobatic ace Tom Moon, aka Mr Magic, gives me a safety brief. It ends with the casual information that he's wearing a parachute and I'm not. This could be quite a ride.

Don't blame aerobatic pilots if they appear a little too black and white. When up is life and down is death, certainty is a necessity, arrogance a bonus. A cool head is the key. Dummies in this sport soon become mummies. There's a very fine line between 'the right stuff' and rightly stuffed.

World War 1 brought very few positives, other than its end and the sport of aerobatics. The art of dogfighting was the ultimate test of man and machine. These days, competitors are still trying to kill each other, but thankfully only on the scoreboard. At the 1998 World Aerobatic Championships in Slovakia, two Aussies (out of 75 competitors) attended the biannual event, with Mal Beard finishing 51st and a delighted Mr Magic 35th, the second-highest placing by an Australian in the event's history, behind Frank Fry who took a medal in the '80s. The overall winner was 50-year-old Patrick Paris, his winning margin as obvious as his nationality.

For what looks like airborne anarchy to the uninitiated, aerobatics is in fact dramatically precise. Tom is throwing me around the sky now and I'm getting RSI in my Adam's apple as we weave from 'reverse half-Cuban' to 'outside humpty', through the 'snap roll' and into the 'horizontal eight'. Tom has threatened to end his routine with his favourite manoeuvre for the novice and the coup de grace for nausea - the 'forward somersault' or 'tumble', which he describes with a chuckle as "like trying to ride a wild horse at negative-four G."

The best insight into the minds of these people is this: Tom's favourite manoeuvre is the one that nearly killed him, the 'knife-edge spin'. And he's going to do it now. "You with me?" he asks before each manoeuvre. This time my "yes" is hazy and delayed. A few seconds later his $350,000 German aircraft, an Extra 300, is rotating on its side, corkscrewing downstairs and losing 400 feet per rotation. Spiralling every three seconds spells a rate of descent of 8000 feet per minute, but tell yourself that once you've finished. As we pull out of the dive we bust seven Gs. That means my 80kg body weighs 560kg as we hit 400kmph heading straight for the ground. If we hadn't stopped the spin where we did we'd have been a picnic rug in six seconds.

"So, how did that manoeuvre nearly kill you?"

Mr magic is calm and factual: "Oh, I just did one rotation too many

"

Insanity appears the most conspicuous attribute of aerobatics pilots, but it's not. Not live ones, at least. It's their precision, quick thinking, physical stamina and the ability to stay one step ahead of their machines which contribute to survival and success. They view their sport as a highly disciplined art form. If you're going to call them stunt pilots, for your own safety do it after they've taken you flying.

Curbing bravado is a must and a skill. Cowboys stick out like third thumbs and dig their own graves. The price of an off-day is extortionate. As Tom explains it, the dangers are obvious: you just have to minimise your risks. "If you're high and fast then mistakes are often recoverable. The rule of aerobatics is never do it low and slow, so if you do have an engine failure you've got tons of energy to push out of it. I have never, ever seen an aeroplane hit the ground and win."

The competition movement in Australia has been around for an accident-free 25 years. Around 60 pilots compete in competitions from state to national championships. But only seven of these fly at the 'Unlimited' level required to be eligible for the Worlds, while the rest spread themselves over the other categories from 'Basic Sportsman' and 'Intermediate' to 'Advanced'. Competitions are fought out in a cubic kilometre of air space; exit this area, defined on the ground by yellow markers, and you're penalised.

If you're in aerobatics for the money, you're out of it. "There's a hell of a lot of money in aerobatics and it's all going out, being spent by the pilots," explains Tom Moon. Sponsorship is next to impossible and the words "prize money" are not in the aerobatic pilot's vocabulary. Even on the world stage. All Patrick Paris received was a medal, the envy of 74 other flyboys and some "oohs" and "aahs" from the crowd.

It is possible to make money from the sport overseas; the entire Russian team and the bulk of the French and US teams are professional, with an intensive air show circuit funding the daredevil hobby of competition. But Australian competitors need real jobs. Tom Moon runs his own accounting firm, while archrival and current 'Unlimited' Australian champion, David Lowy, is also busy running a business to keep his plane in the sky. Some competitors still fly for a living, but usually the right way up.

The machines are as eccentric as the pilots who fly them. Planes cost a small fortune to purchase, but once bought they're relatively inexpensive to keep. Routine maintenance on an Extra 300 will set you back around $10,000 a year with an additional $5000 for insurance. The six-cylinder, nine-litre engine eats 120 litres of fuel per hour and provides a cruise speed of around 340kmph.

There are three main types of aircraft used at the Unlimited level, and it's their superb aerodynamics that earn them this distinction. The Russian Sukhoi, the French Cap and the Extra 300 are awesomely controllable and alarmingly manoeuvrable planes. In a snap roll the Extra can roll left or right at 500 degrees per second. Made of carbon fibre, the planes are incredibly strongly built to withstand the massive G loads in most manoeuvres. With a G limit range of plus or minus 10, the chances of structural failure - a pilot's worst fear - are minimised. But just because the plane can handle it doesn't mean the pilot will.

At the recent Worlds, Tom lost his sight in both the 'humpty' manoeuvres. The humpty requires the aircraft to pull through an exaggerated looping dive; it isn't uncommon to endure eight Gs for up to five seconds. During sustained bouts of high G force the optic nerve is the first to quit; starved of blood and oxygen, the vision greys to black as the body approaches a phenomenon that few people have survived - G lock. This has earned the humpty and similar manoeuvres the infamous label of 'sleeper manoeuvres' because they're guaranteed to put the pilot into unconsciousness. Fortunately, once the G load diminishes, unless you've reached G lock the vision returns - and Mr Magic woke up just in time to see his name next to #35 on the Slovakian scoreboard.

In a sport of egos, there is very little one-on-one rivalry or bitching during competitions. "There are plenty of egos but no egos without talent," says Moon. "Everyone appreciates just how bloody hard it is."

Competition events are divided into four sections. The first of these is essentially a warm-up. Stage 2 is the free sequence, where pilots fly their favourite manoeuvres. Then it gets tough. Stages 3 and 4 are termed the 'Unknowns'; often as little as 24 hours before competition, pilots are given a diagram of the manoeuvres they must perform, some of which they might never have flown. They're not allowed to fly them until it's their turn to compete, so pilots will do a 'dirt dance' on the ground to try and absorb the directions of the manoeuvres. At competitions, you'll often see contestants shuffling around strangely and waving their hands in the air as they mentally rehearse their routine.

"In my first World Championships in the second Unknown, I'd never flown 11 of the 13 manoeuvres I was required to do," explains Moon. His face turns to a smile as he says proudly, "And I only zeroed the tailslide." The two Unknowns are considered so mentally and physically demanding that organisers must ensure that no pilot flies them both on the same day.

Aerobatics is one of few sports with no significant physical advantage between men and women. The planes require no great strength to fly, and Australia has already had a female aerobatics champion in Bonny Henderson. The Russian woman pilot who finished third overall in Slovakia has the frame of a ballerina, a profession she used to pursue. The moves afoot to make the Worlds a single competition for men and women are considered timely by most contestants.

Sure, pilots have been known to die doing aerobatics. Overall, however, the sport is surprisingly safe. Question a pilot on near misses and you're more likely to hear Houdini-like sagas involving straight and level flying. More pilots die getting from A to B than in 'knife-edge spins'. Four days after the 1998 Worlds, Swiss ace Christian Schweizer flew into a mountain on a navigational run in Switzerland. He and son Daniel died instantly.

Mr Magic's throwing everything at me now. His routine "feeling okay?" inquiries from the rear seat are being answered less and less enthusiastically as nausea surges. Remember to always take your own plastic bag and rubber band with you. And make sure the bag isn't see-through!

The anarchist is in my ears again. "Gotta leave you with the somersault," says Tom. Climbing into it, the G is high and positive. My blood is in my feet. Negative G hurts a lot more than its opposite, and as we push over the top we clock four of them. Suddenly the nose drops, the engine weighs 300 kilos and the gyroscopic procession of the Extra brings the tail and us over the top of its diving nose. We go over twice: guts, heads and feet in a washing machine. Sure, it's done with precision, but it feels like the wipeout from hell. The violence goes on too long and I'm sure Tom's lost control of the airplane. Up is down and left is right. The sky is brown and the Earth blue. I'm going to die now and it's going to hurt.

For the first time high Gs are a relief; it means we're diving and we've made it out. Alive. Tom pulls the wings level. "Let's go home," he says. It's impossible to embrace him, strapped so tightly to the front seat.

With the kiss of rubber and concrete our bird rolls to a stop. The unmovable Earth feels good underfoot after witnessing sport's dizziest limits.

Category

Category